De Landa Alphabet

Upon the arrival of the Spanish in the heart of Maya civilization, they were baffled by the rich and complex culture that existed among the natives. Monumental structures such as temples were carved with inscriptions that depicted the people's unique cosmological and philosophical worldview. However, to the Spanish, all this was nothing but a mere manifestation of the Devil. The Catholic Church quickly moved to suppress and convert the Indigenous people to Christianity. One of the most infamous efforts came from Fray Diego de Landa, a Spanish Franciscan friar known for his extreme views against Maya spirituality and their books—codices. Unaware of the cosmological and philosophical perspectives of the Maya, de Landa simply labeled such knowledge as superstition and demonic.

On July 12, 1562, de Landa ordered an unauthorized "auto-da-fé" inquisition in the town of Maní, Yucatán. This campaign involved interrogations through forced confessions, torture, and demanded that all manuscripts (codices) containing the "lies of the devil" and idols (stela) that represented "demons" were to be burned in public. Centuries of culture and history destroyed by these simple words, he erased a rich pantheon of deities and labeled a complex system of writing into one simple monolithic thing—the Devil.

Many members of Diego de Landa's convent and other clergy actively criticized and condemned his actions, since the Church had not sanctioned the Inquisition. Bishop Francisco de Toral, who had just been appointed Bishop of Yucatán in the same year, spoke out against the abuse that was inflicted upon the Maya. After hearing testimonies from Maya survivors, Toral denounced de Lands's abuses against "baptized Christians" as unethical. Toral's intervention defended the Maya in Church proceedings and caused de Landa to return to Spain in 1563 to stand trial for conducting an illegal inquisition.

Strategically defending himself, de Landa managed to win the trial in Spain. Not only did he justify his actions as necessary for preserving Christianity in the New World, but he also had support from allies within the Church and Crown, which helped advocate his argument. Although his methods were brutal, he claimed himself as a loyal missionary carrying out his religious obligations. During this period, Spain valued results over ethics and primarily focused on maintaining colonial order, and cultural destruction was tolerated if it led to Christian domination. Therefore, de Landa's extreme methods were seen as an "effective" path to eliminating idolatry and were in line with the priorities of the Church and Crown. De Landa was absolved of wrongdoing and was later appointed the second Bishop of Yucatán in 1573 by King Philip II of Spain, after the passing of Bishop Francisco de Toral.

Ironically, after he arrived in Yucatán as Bishop, he later wrote his book, Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán. He began recording Maya culture with the help of locals, and he was able to preserve valuable information on the Maya, such as religious practices, and kept a record of the Maya calendric cycles. He also became the first to have ever attempted to document the Maya language. Assuming that the glyph system works as the alphabet of Spanish or Latin, he drafted up his version of the "Maya alphabet" known today as the "de Landa alphabet". Mistakenly pairing phonetic sounds of the Maya language to the single letter Spanish alphabet, he correlated each sound with Maya glyphs, thinking that Maya script was an alphabetic system

Although his work proved to be inaccurate, the de Landa script paved the way for deciphering the Maya code by future Mayanists. In the 1950s, Russian epigrapher Yuri Knórosov reexamined de Landa's manuscript and realized that the recorded "Maya alphabet" was indeed syllables, not letters. Knórosov's approach was that this script was never meant to be written like the European alphabet, but instead, it's a system made up of symbols of syllabic writing, like that of Egyptian or Japanese scripts. Knórosov concluded that Maya script is logosyllabic, which combines syllabic signs (like ha, ka, la, ma) with logograms (symbols representing whole words). His groundbreaking work laid the foundation for modern Maya epigraphy; today, thanks to Knórosov, over 90% of the Maya script has been successfully deciphered.

The Codices

figure 1

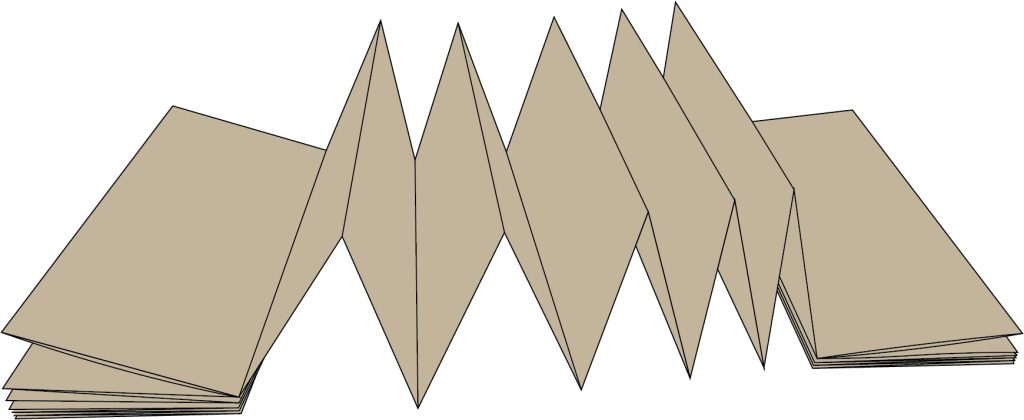

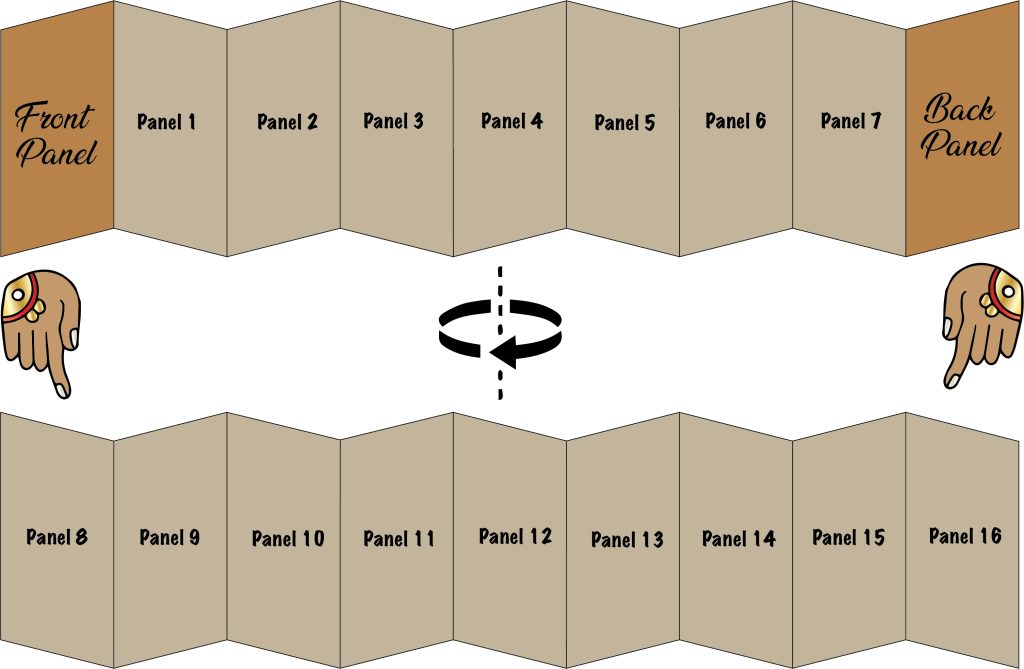

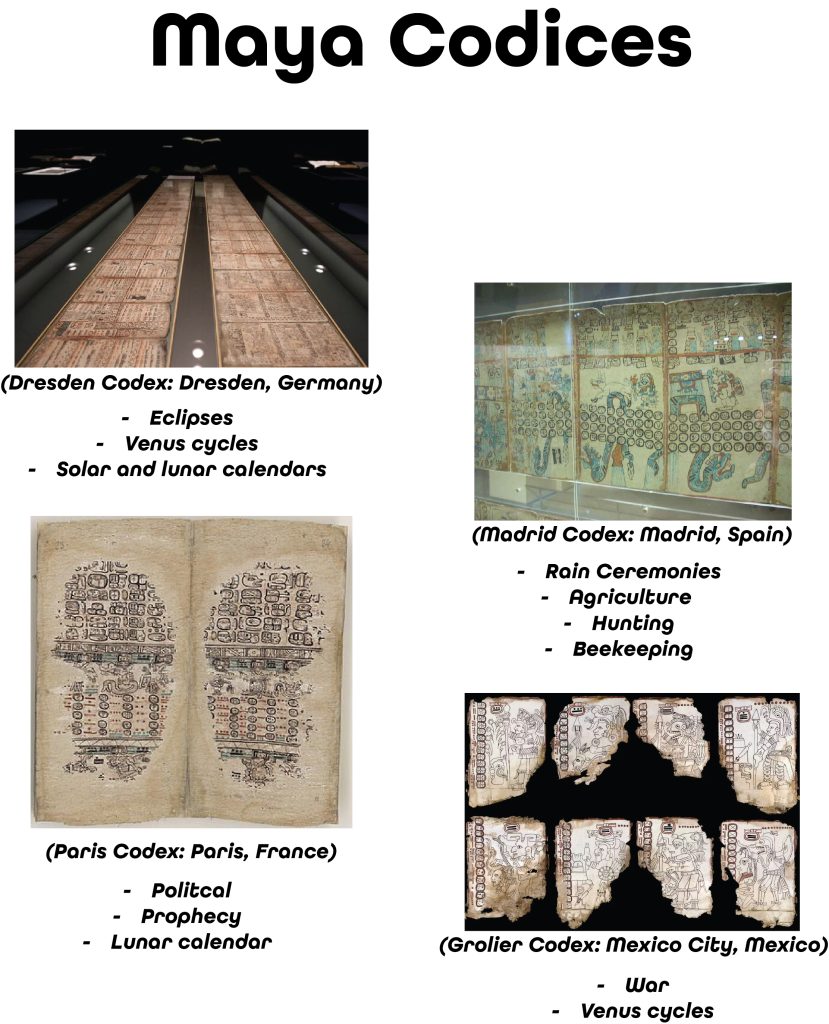

The surviving Maya books or "codices"—Dresden, Madrid, Paris, and Grolier— are the only four known testaments of Maya knowledge that offer a rare glimpse into the cosmological and philosophical worldview of a civilization robbed of this knowledge. These screenfold manuscripts were made from "amatl" bark paper, which was coated with limestone plaster and folded like an accordion. (Figure 1)

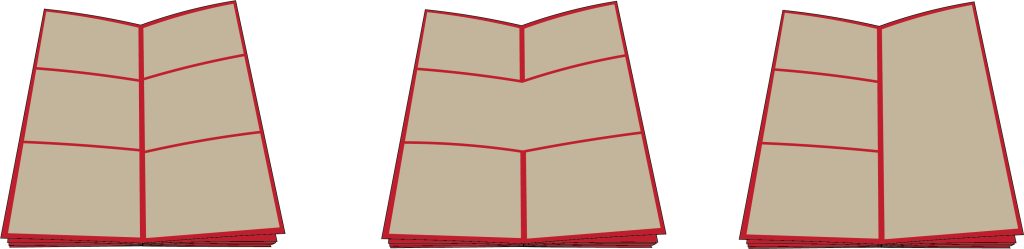

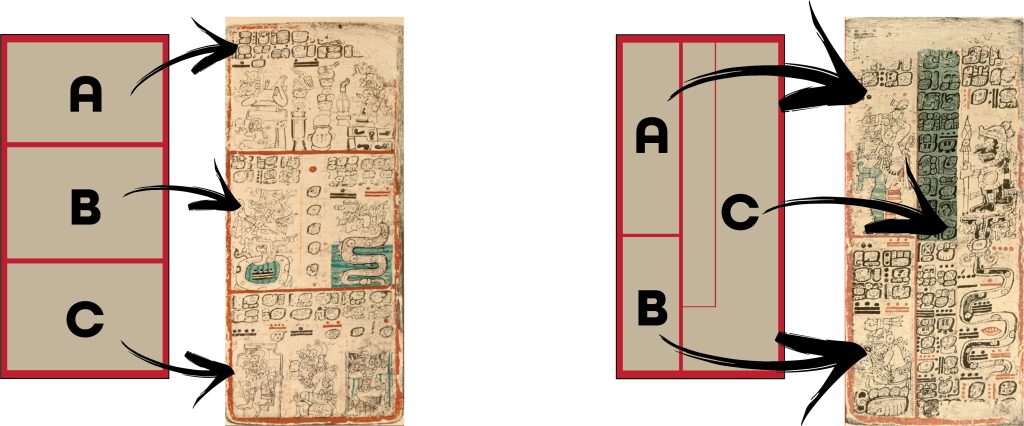

Each page is organized into almanacs and tables. (Figure 2) They demonstrate how the Maya once used sophisticated calendric cycles to predict celestial movements and coordinate ritual ceremonies. Each codex served its purpose. Some were used to track various planets/stars, and others were used to predict agricultural events or social/ritual activities. These codices served as an instrument for priests, day-keepers, and only the noble class had access to them. Evidence shows that several scribes were involved in creating these codices because the technique used with glyphs varies throughout each codex.

figure 2

Understanding the Format

Figure 3

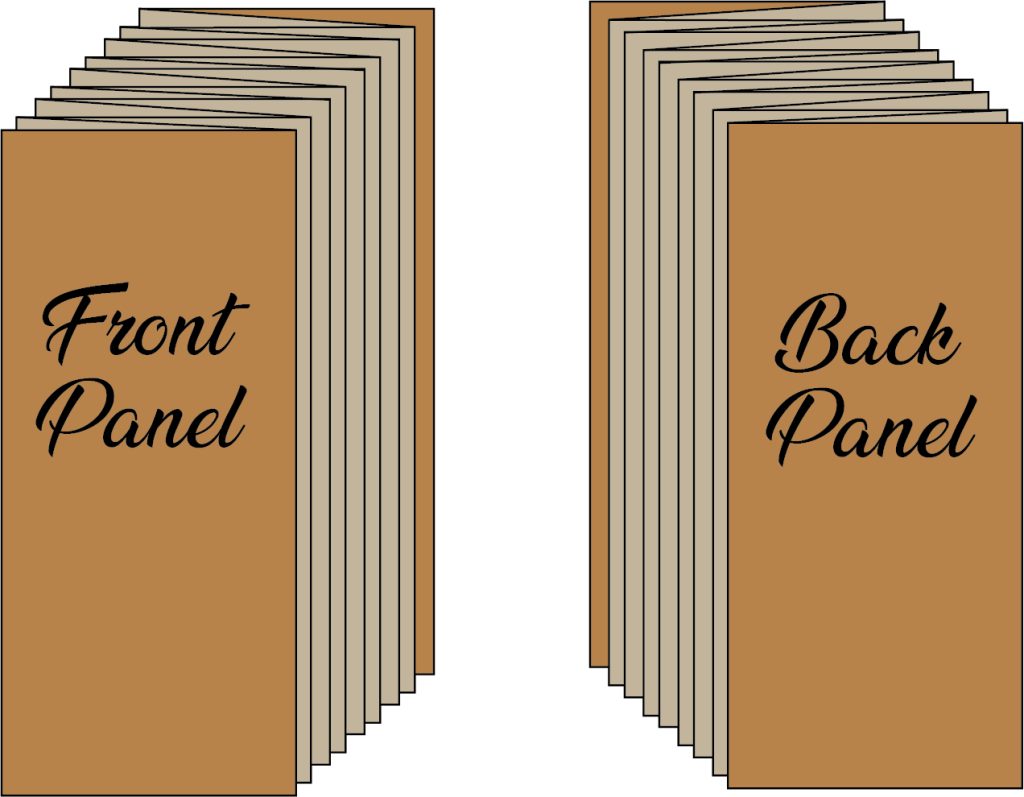

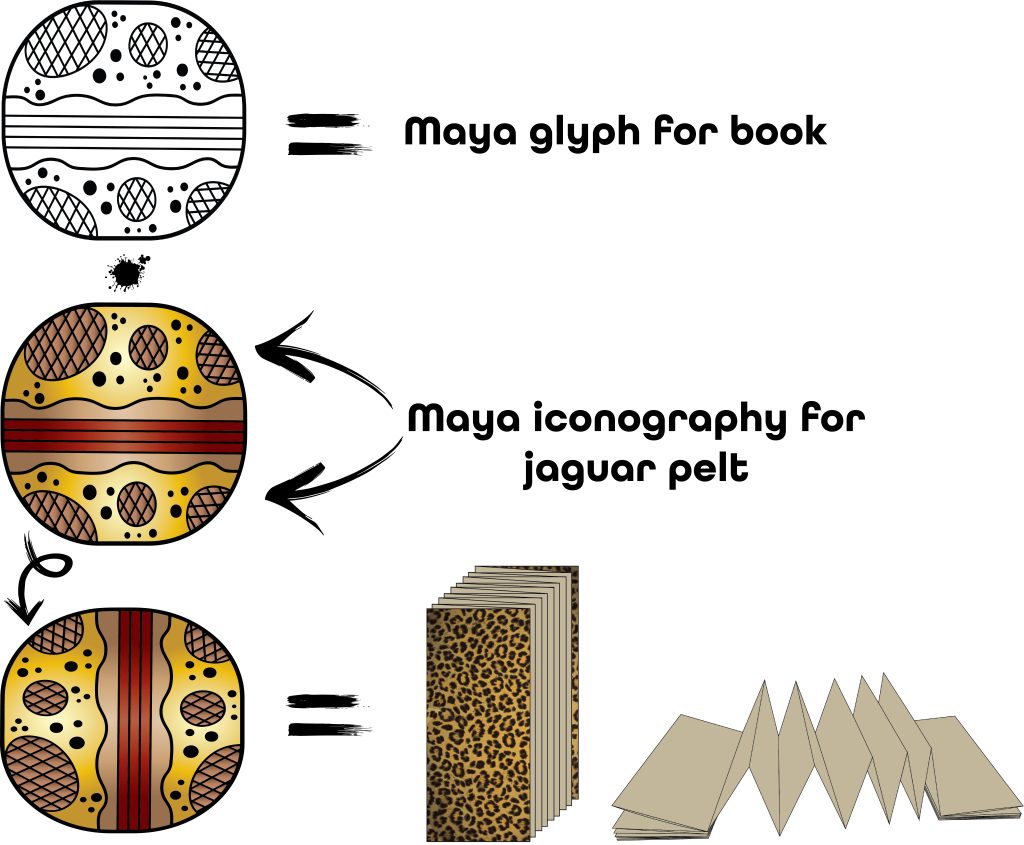

Maya codices are screen-folded manuscripts made from bark paper, typically in the form of a rectangular book. Multiple sheets were joined and folded in such a way that they appeared like an "accordion". (Figure 3) The front covers of Maya codices may have been wooden boards coated in stucco and possibly decorated with plant-based pigment. Although no surviving codex has its original cover, evidence from the Madrid Codex shows that it was once bound to another volume. The Dresden Codex also shows evidence that it once had covers, but since the covers would have been from organic materials, they would have decomposed over time. Regardless, the Maya codices were most likely to have been bound in between covers decorated in vibrant pigment and possibly wrapped in jaguar pelt since the jaguar was seen as a powerful symbol for power and divine authority by the Maya. The codices were also commonly depicted with a jaguar pelt on vases. The Maya glyph for "book" is also depicted as a bundle sandwiched between two layers of "jaguar skin". (Figure 4) The concept of wrapping sacred knowledge in jaguar skin would align much with ancient Maya practices since these codices were considered sacred items and used in rituals by high-ranking priests.

Figure 4

Figure 5

These manuscripts were not read linearly like modern books—they were consulted section by section. When unfolded, their length can reach several feet. Both sides of the folded manuscript were painted with individual panels. (Figure 5) Each panel was generally read from left to right, top to bottom. But since the Maya codices are not purely textual, the panels were often framed into sections using a red pigment to mark the narrative flow. (Figure 6)

Figure 6

Codical Style

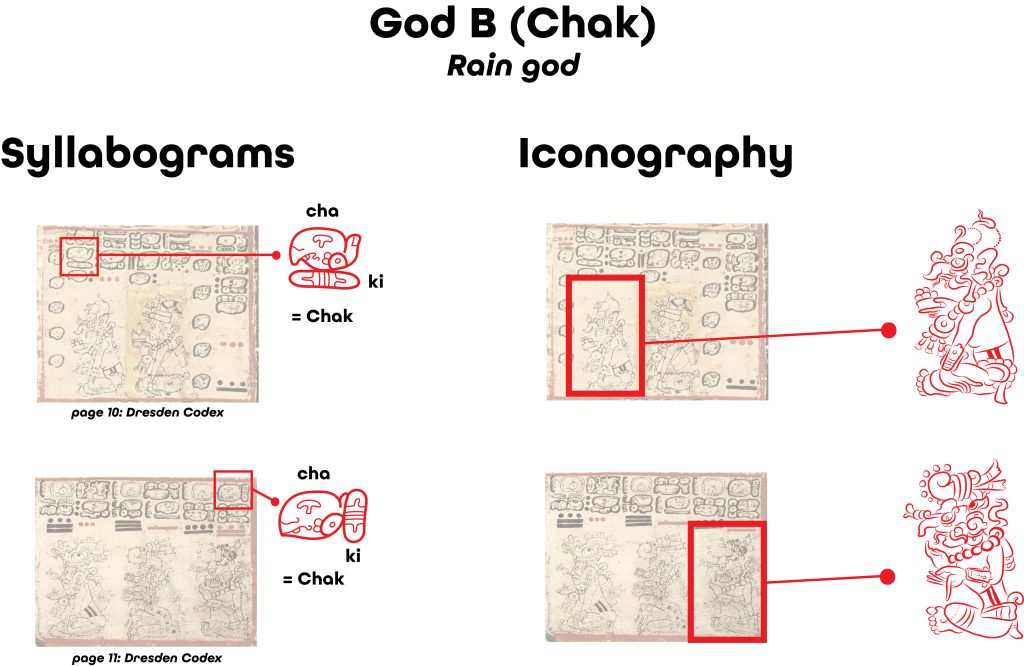

Since the Maya recorded their culture using glyphs, their writing appeared in various forms, and the codices were no exception. They incorporated the use of syllable glyphs (the combination of phonetic sounds) and logograms (glyphs that represent a word or concept). The use of iconography was also common to help depict "deities" in the Maya codices. (Figure 7) What distinguishes the glyphs found in the codices from those carved into stone is the use of fine brushes, typically made from animal hair or plant fibers. This allowed scribes more freedom, allowing them to stylize the glyphs, which gave the glyphs a calligraphic appearance. This form of glyph style is known as "Codical style". It is often written in black and red ink and commonly found in abbreviated forms. This style is also found in ceramics from the Late Classic period.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 1-5: Gaspar Tomas, 2025.

Figure 6: Förstemann. Dresden Codex, p. 48, p. 64, http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/pdf/dresden_fors_schele_all.pdf . Accesssed 2025.

Figure 7: Förstemann. Dresden Codex, pp. 10-11, http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/pdf/dresden_fors_schele_all.pdf . Accessed 2025.

"Maya Codices" Figure:

Day, Joel. "Archaeologists Taken Aback by the Unravelling of 800-Year-Old Mayan Text." Express.co.uk, Express.Co.Uk, 20 Oct. 2023, www.express.co.uk/news/science/1825781/archaeology-ancient-maya-dresden-codex-spt.

"Paris Codex." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation 28, May 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ParisCodex.

Elizabeth Graham, Professor of Mesoamerican Archaeology. "Grolier Codex Ruled Genuine: What the Oldest Manuscript to Survive Spanish Conquest Reveals." The Conversation, 1 Aug. 2025, theconversation.com/grolier-codex-ruled-genuine-what-the-oldest-manuscript-to-survive-spanish-conquest-reveals-67941.

"Category:Madrid Codex." Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Madrid_Codex. Accessed 5 Aug. 2025.